| LAND USE and HOUSING

"The least fallible of city planners is the free market."--Bernard

Siegan, in Land Use Without Zoning

Government "solutions" to land use and housing problems have been primarily political moves which imposed Large costs upon the middle- and low-income people who could Least afford them. Environmental nuisances have been permitted to continue and even expand, but non-aggressive uses of Land are prohibited in order to satisfy politically powerful minorities. Studies indicate that zoning boosts renters' costs ten to fifteen percent, in addition to imposing other hard-to-quantify burdens. Rent controls, building codes, rehabilitation subsidies, and public housing have all hurt low-income housing residents rather than helped them.

Land Use The laws of trespass and nuisance exist

for the purpose of marking out the proper boundaries between neighbors.

They are instruments for keeping the peace. As such, these laws need

to evolve and grow as people invent new ways of trespassing upon each other.

|

TABLE 1

AVERAGE ANNUAL RENTAL COSTS FOR TWO FAMILY SIZES AND THREE LIVING

STANDARDS -

HOUSTON AND DALLAS

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| 4-Member families

Autumn, 1966 Spring, 1967 Spring, 1969 |

$872.00

931.00 |

$973.00

989.00 |

$1,051.00 1,086.00 1,175.00 |

$1,243.00 1,277.00 1,340.00 |

$1,575.00

1,721.00 |

$2,369.00

2,642.00 |

|||

| Retired couples

Autumn, 1966 Spring, 1967 Spring, 1969 |

628.00

662.00 |

636.00

744.00 |

754.00 790.00 878.00 |

818.00 856.00 1,039.00 |

1,757.00

1,855.00 |

1,756.00

1,997.00 |

|||

| Sources:U.S. Dept. of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bulletins

Nos. 1570-1, 1570-5 and supplement; 1570-4, 1570-6 and supplement.

Reproduced with permission from: Bernard Siegan, Land Use Without Zoning (Lexington, Mass., D.C. Heath and Co., 1972), p. 118. |

| housing supply. Moreover, each new home added to the housing

supply would then make possible an average of three-and-one-half succeeding

moves as others "move up" to newly-vacated housing.13 People do seem

to know where their interest lies with regard to zoning. In the rare

cases where local laws have allowed zoning to be put to a vote, all except

the most upper class neighborhoods have rather consistently voted against

it.14 Rural zoning boards as well as urban practice discrimination:

their ordinances often restrict mobile homes, household businesses, and

small hunting cabins (sometimes called "the second home of the middle class").

Farmers complain of being prevented from retiring to a house trailer on

their land when the kids take up farming.15

Housing There is only one way to make more and

better housing available to those who want it: increase the supply. And

there is only one way government can increase the housing supply without

robbing from the stock of other goods people value: eliminate government

obstacles which make housing hard to produce and buy. Yet local government

policies inspired by the federal Housing Act of 1949 have exhausted just

about every conceivable way of evading these simple facts. In their

tinkerings with the housing industry, local governments have made much

political mileage but, as we shall see, solved few problems. Instead, housing

policies have foisted inconveniences and high costs upon the very people

these programs were supposed to help.

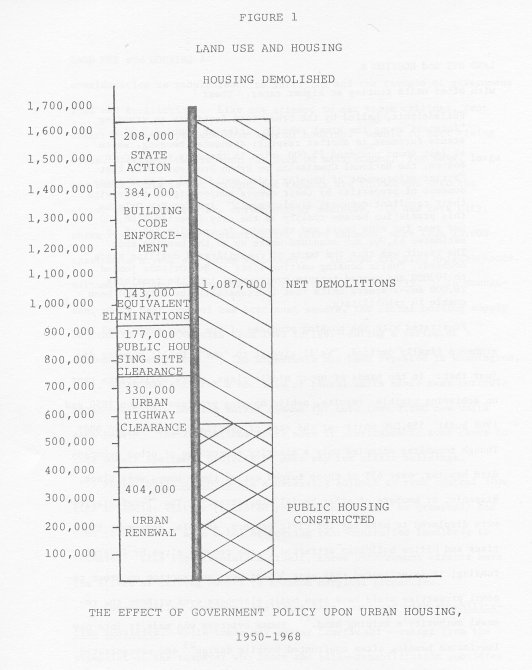

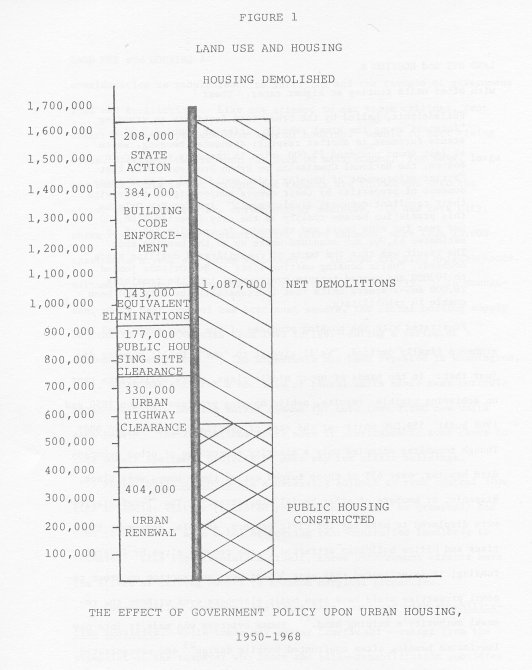

Philadelphia, hailed by the Urban Land Institute as standing "foremost among the great rebuilt cities of America," also stands foremost in another respect: abandoned housing, which at last count numbered 25,000 units in the city proper. In Boston, the National Commission on Urban Problems found thatFrustrated with the housing problems of the poor, many local governments finally decided, "We'll give it to 'em!" Public housing did just that. In the hands of upper middle class, white politicians bent on achieving visible results, public housing programs between 1950 and 1968 built 559,000 units--at the cost of demolishing some 1,646,000! Though nonwhites occupied only a minority percentage of urban substandard housing, over 65% of those turned out of their homes were black, Hispanic, or members of other racial minorities.21 The "beneficiaries" were displaced to make way for civic centers, schools, apartment high-rises and office buildings attracted to the renewal sites by federal funding; it is estimated that over 50% of new construction on urban renewal properties would have been built elsewhere even without the renewal authority's helping hand.22 Those evictees who made it into new low-income housing often confronted hostile design23 and concentrated exposure to juvenile delinquency. Economist Richard Craswell has observed that "since occupancy was limited to low-income families, turnover rates were high; as families increased their income, they were |

| SOURCE: | Commission on Urban Problems, Building

the American City, pp. 82-83. Estimates of demolitions from Urban

Renewal, Urban Highways, Public Housing Site Clearance, and Equivalent

Demolitions are those of the Commission; other estimates are based on National

Association of Home Builders figures cited in the Commission's report.

Public Housing figures are from the 1971 HUD Statistical Yearbook,

table 150, p. 145.

While most figures have been adjusted to cover a common period of time (roughly 1950-1968), in the case of the Code Enforcement and State Action estimates this was impossible. Since these figures were available only as far back as 1960, the net demolition figure is actually an understatement. |

|

| Reproduced with permission from Richard Craswell, The Failure Of Federal Housing (Washington, D.C. ACU Education and Research Institute, 1977), p. 8. | ||

| forced to move out--and the lack of stability contributed to the

poor sociological environment."24 Those who were left on the waiting

list simply had to scramble for a place to sleep, gritting their teeth

under brunt of inflated rents and poorer conditions in a shrunken housing

supply.

Public housing was to have cost less than private; but in general it has cost 20% more. Reports Graswell: "In Washington, D.C.... the true monthly rent (not counting the subsidy reduction) of a one-bedroom public housing apartment was $32 more than a comparable private unit; in Pittsburgh, the difference was $40; in Seattle, $64." 25 In reaction, authorities have toyed with a few last ideas. The "Turnkey" program of subcontracting public housing construction and management to private corporations succeeded somewhat in shaving costs. Interest subsidies for low-income housing purchasers were tried in Boston until, after three years, over eighty per cent of the loan customers were in default. So after all has been said and done, what could remain but to give the housing-needy the money directly? This is the idea behind housing vouchers: grants to landlords and homeowners to purchase improved housing. Though this subsidy technique sheds some of the bureaucratic costs associated with previous housing panaceas, it is subject to the same general pitfalls. An example will illustrate. If we give John Doe $1,000 upon the sole condition that he spend it on housing, it is likely that he will be more eager to buy housing than if the money were really his own and he could use it to buy food, clothes, or a new car. Knowing this, landlords and building contractors will be less likely to provide additional housing without taking advantage of the opportunity to raise prices and inflate costs. This is fine with John Doe; even if he has to spend $1,000 to get improvements previously worth only $500, it's all free to him anyway. But what about other people who receive no subsidy? The effect of John Doe's "easy money" on housing costs is felt by them, too. And with each escalation the cost of subsidies to the taxpayer rises even faster, as a broader base of people need help.26 The result of such programs may be observed in Sweden, where 90% of the housing receives government aid of one sort or another,27 hundreds of homeless people compete for each vacant unit,28 and a young couple may go six or seven years before getting an apartment all their own. By any index, this is no way to solve the housing problem. Libertarian Proposals What will Libertarians do about land use

and housing?

|

TABLE 2

LAND USE PLANNING, COERCIVE AND VOLUNTARY MEANS

|

|

|

||

| * | Zoning | * | Landowner planning within a framework of land and environmental property rights |

| * | Esthetics, "open space," and sign controls | * | Voluntary covenants to restrict land uses |

| * | Subdivision controls | * | Private agreements concerning the availability of utilities and access to roads |

| * | Government agricultural districts | * | Voluntary covenants concerning conflicts between farmers and their neighbors |

| * | Building codes | * | Building guarantees |

| * | Flood insurance-related building standards imposed over entire flood-prone area | * | Agreements to provide private flood insurance only to those abiding

by insurers' standards

(and leaving others alone) |

| * | Eminent domain | * | Skilled long-term purchasing

and aggregation of properties on completely voluntary basis |

| * | Urban renewal and "community development" | * | Redevelopment by individuals, corporations, improvement associations, and the developers of "proprietary communities" such as hotel complexes, shopping malls, etc. |

| LAND USE and HOUSING NOTES |

| 1. | "Russian Mayor Likes Houston," AREA Bulletin (December 1975), p. 3. The same article noted that "it should be interesting to hear where Vasily Isaev and colleagues will place the blame for New York's financial crisis." Moscow's mayor was soon thereafter quoted by the New York Times that Moscow could never go bankrupt like New York because Moscow did not have capitalist system. |

| 2. | New York News World, February 10, 1977. |

| 3. | See R. Dale Grinder, "The Industrial Revolution and the Law of Nuisance and Smoke," Fourth Annual Libertarian Scholars Conference, October 1976. Cf. Morton Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1977). |

| 4. | Horace Gay Wood, A Practical Treatise on the Law of Nuisances in Their Various Forms (Albany, N.Y., 1875, Ist edition), p. 476; cited in Grinder, op. cit. |

| 5. | See Ernst Freund, The Police Power, Public Policy, and Constitutional Rights (Chicago: Callaghan, 1904). |

| 6. | 272 U.S. 365 (1926). An earlier case concerning Boston's height control ordinance is Welch v. Swasey, 214 U.S. 91 (1909). |

| 7. | John McClaughry, "The New Feudalism," 5 Environmental Law

(Spring 1975), p. 675.

Historically, it is well recorded that zoning promoters Ernst Freund and Edward Bassett, among others, undertook an extensive campaign to discredit the notion that police power regulations such as zoning were limited to nuisance-type application. See, e.g., Seymour I. Toll, Zoned American (New York: Grossman, 1969), p. 264; and Richard F. Babcock, The Zoning Game: Municipal Practices and Policies (Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin Press, 1966). Cf. Edward M. Bassett, Zoning (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1940). |

| 8. | McClaughry, "The New Feudalism," 5 Environmental Law 675. |

| 9. | Jane Jacobs, The Economy of Cities (New York: Random House, 1969), p. 105. |

| 10. | See Bernard Siegan, Land Use Without Zoning (Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books, D.C. Heath & Co,. 1972), pp. 117-120. |

| 11. | Ibid., Chapter 6. |

| 12. | The quote is from Robert Venturi, et. al., Learning From Las Vegas (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press,, 1972). Spring's opposition to strict esthetic controls is discussed in William D. Burt, "More Than One Way to Skin a City," AREA Bulletin (May-June 1977), p. 5. Cf. R. L. Bjornseth, "Environmental Appearance Council Formed," AREA Bulletin (January-February 1977), p. 1. |

| 13. | Siegan, "No Zoning Is the Best Zoning," in No Land is an Island (San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies, 1975), p. 163. For a fuller treatment, see Siegan, Land Use Without Zoning, pp. 93-95, which cites John B. Lansing, Charles W. Clifton, and James N. Morgan, New Homes and Poor People: A Study of the Chain of Moves (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1969). |

| 14. | Siegan, "No Zoning Is the Best Zoning," p. 160. |

| 15. | For an investigation of opposition to rural zoning, see William D. Burt, "Zoning Fight Spreads in Western New York State," AREA Bulletin (January 1976). This article reviews the several votes against zoning proposals recorded in Western New York 1972-1975. The AREA Bulletin has carried occasional articles reporting such votes against zoning in the Midwest, and John McClaughry discusses the popular sentiment against land use control in Vermont, in "How to Fight Land Use Planners," Reason (October 1976), p. 12. |

| 16. | Senator Thomas F. Eagleton, "Why Rent Controls Don't Work," The Reader's Digest (August 1977), p. 111. |

| 17. | "Our Dying Neighborhoods," New York Daily News, August 1. 1977. |

| 18. | Richard Craswell, The Failure of Federal Housing (Washington, D.C.: American Conservative Union Education and Research Institute, 1977), P. 9. |

| 19. | Eagleton, op. cit., p. 109. |

| 20. | Craswell, op. cit., p. 10. |

| 21. | Ibid., p. 6 and p. 8. Cf. William G. Grigsby, Housing

Markets and Public Policy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania

Press,

1963), p. 258. |

| 22. | Martin Anderson, The Federal Bulldozer (Cambridge: MIT Press,

1964), p. 222. |

| 23. | The St. Louis Pruitt-Igoe Project proved such an abject design

failure that after several yea';s of low occupancy (down to 20%) it was finally dynamited by the using authority. |

| 24. | Craswell, op. cit., p. 11. |

| 25. | Richard F. Muth, Public Housing: An Economic Evaluation (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1973) p. 39; cited in Craswell, op. cit., p. 12. |

| 27. | U.S. News and World Report, June 7, 1971, p. 48; cited in Craswell, op. cit., p. 16. |

| 28. | Sven Rydenfelt, "Sweden Rent Control Thirty Years On," in Verdict on Rent Control: Essays on the Economic Consequences of Political Action to Restrict Rents in Five Countries (London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 1972), p. 77. |

| 29. | Civil Engineering-ADCE, December 1976 |

| 30. | Chester County, Pennsylvania Stormwater Management Bulletin. (1977) See also William D. Burt, "Erosion Arbitration Proposed," AREA Bulletin (January-February 1977). p. 5. |

| 31. | CDS address is 140 West 51st St., New York, NY 10020. |

| 32. | John McClaughry, "Farmers, Freedom, and Feudalism," South Dakota Law Review, Vol. 215 #3 (Summer 1976), p. 521, his note 126. |

| 33. | CLS address is 200 Park Avenue South, #911, New York, NY 10003; AREA address is P.O. Box 906, Greenwich, CT. 06830 |

| 34. | Siegan, "No Zoning Is the Best Zoning," p. 166. |

| 35. | Ibid., p. 159. |

| 36. | For further details, see Siegan, Land Use Without Zoning, Chapter Two. |

| 37. | Proper measurement of such damages to be assessed could be facilitated if courts were to require parties to a covenant to specify the type and amount of restitution ( "damages" ) they expect to pay should they default on performance of the covenant. |

| 38. | This point originates with Murray N. Rothbard, cited in note 24 in Williamson M. Evers, "Toward a Reformation of the Law of Contracts," Journal of Libertarian Studies, vol. 1, #1, (Winter 1977), pp. 3-14. |

| 39. | Siegan, Land Use Without Zoning, p. 236. |

| 40. | McClaughry, "Farmers, Freedom, and Feudalism," p. 159. Cf. Allison Dunham, "Private Enforcement of City Planning," 20 Law & Contemporary Problems 463 (1955). |

| 41. | Craswell, p 1) @20 |

| 42. | New York City building inspectors have become so brazen about their corruption that their union's attorney recently denounced an informer working for a grand jury as "Not a lion, but a worm." The union demanded reinstatement of over 100 city building inspectors fired for bribe-taking since 1975. "Union Burned by Bribe Spy Files Suit," New York Daily News, April 26, 1977. |

| 43. | Craswell, p. 20. |

| 44. | Present federal subsidies for flood insurance require that municipalities impose building codes upon all, not just purchasers of the insurance. Libertarians suggest that building codes may very well have a role to play in free market flood insurance, but that they could only be applied to those who voluntarily participate in such a program. On flood insurance generally, see A Flood Insurance Alternative, Position Paper #1 of the Association for Rational Environmental Alternatives (April 1977). |

| 45. | Craswell, p. 3. |

| 46. | Anderson, The Federal Bulldozer, pp. 208-213. |

| 47. | John McClaughry, "Recycling Declining Cities: Give the People a Chance!", AREA Bulletin (September-October 1977). See also forth- coming article in The Urban Lawyer (Spring 1978). |

| 48. | A recent conference, "Recycling the City: The Entrepreneur as Hero," underscored the facts about private urban renewal in unzoned Houston. Proceedings available from the conference's sponser, the Association for Rational Environmental Alternatives. ( See note 41 ). |

| 49. | Jane Jacobs, The Economy of Cities, p. 199; cited in Craswell, p. 21. |

| Chapter 2 |

|